December 21, 2022

"I'm so excited for this exam," said no person ever.

Except, this year, I did.

So did Mr. Martin and Mrs. Carmichael.

And many of the students in the LABS cohort. They were getting pizza, but that was only part of the reason.

This time of year, in most other rooms, students are sitting silently, in rows, swirling pencils around bubbles, recalling what they've learned over the semester. In LABS, however, students were celebrating. Asked to identify areas where they still had questions, instead of knowing, Ms. Carmichael and Mr. Martin invited the class to show off their curiosity.

In the weeks leading up to this day, students identified--as their focus--an unanswered question they had about something they studied that semester. Then they selected a systemic approach, chose an area of inquiry to guide their research, and designed their own interactive art installation to study it. The installations were meant to provide a window into some aspect of their question, and they opened up those windows with an emic audience. Or, in other words, with their classmates.

Once the ideas were drafted, students used a critical friends protocol designed to push their thinking. In this way, collaboration didn't exist through the lens of a group project; instead, students tasked with a similar anthropological quest felt a sense of commitment to the community for which they were part, and they gave feedback with the intent of helping their peers make every project better. No one wants to take part in boring projects, so making other projects better resulted in a better experience for everyone.

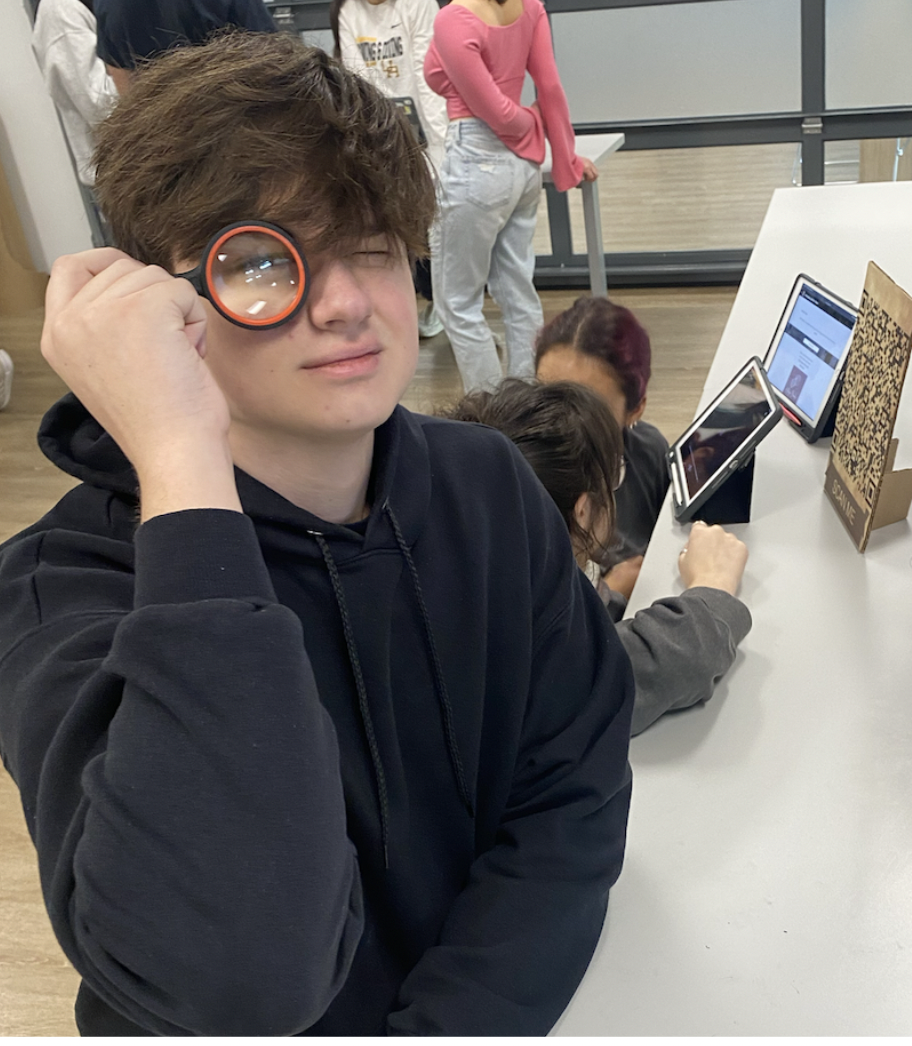

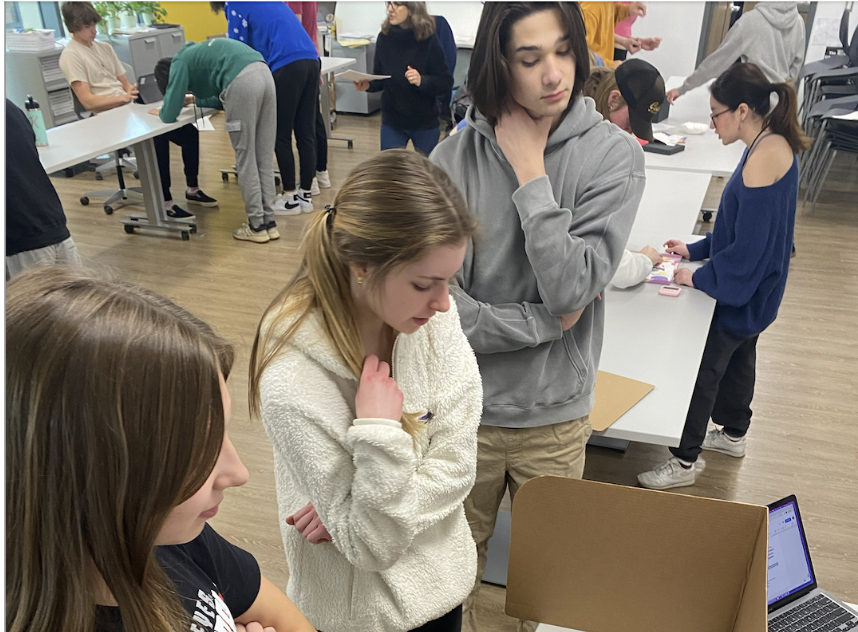

On the day those projects came to life, the room buzzed with energy. Tables were shifted to allow people to move, and the room was loud, lively, full of laughter, puzzles, discussions, activities, and risk-taking.

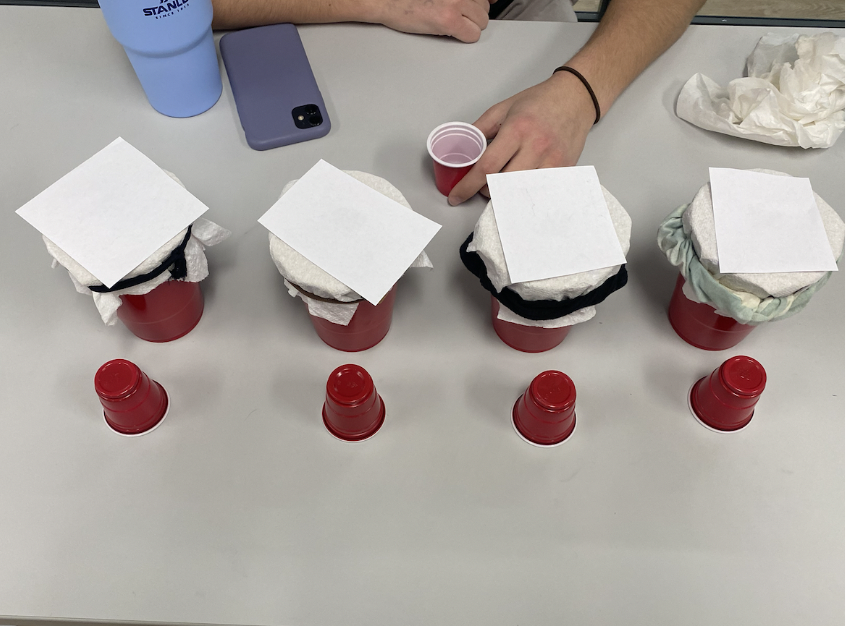

In one of the installations a student asked his peers to draw a perfect circle with a 3 inch diameter. He gave them a bin full of supplies and told them they had a minute and a half to complete the task. At the bottom of the bin, he placed a box, upside down, containing a protractor.

If students had dug through the bin, they would have found the protractor, and drawing the circle would have been much easier. Instead, all but one group set out to create their own makeshift protractor out of string, tacks and rulers--items on top of the pile--and none of them succeeded in either perfection or completion.

"I was rushed," I heard a student say. "Why did you give us so many things we didn't need when we didn't have time to figure it out?"

One group did find the protractor, but they drew a circle that was off the mark. In a moment of panic--with seconds ticking away--they confused diameter and circumference, so even though they took the time to dig, their long-term memory hadn't retrieved the proper background knowledge to make use of the tool they found.

The installation designer smiled. His goal was to show what happens when people under pressure have access to too many things--some that are useful, others that are not. His idea stemmed from an ethnographic text they read called Standing in the Need about Hurricane Katrina relief, and how relief supplies weren't always packaged according to what people needed, or organized in a way meant to help those beneath the weight of stress. Survival chances aren't equal in that situation, and he wanted to see what happened when he simulated, on a very small scale, what survivors had to face.

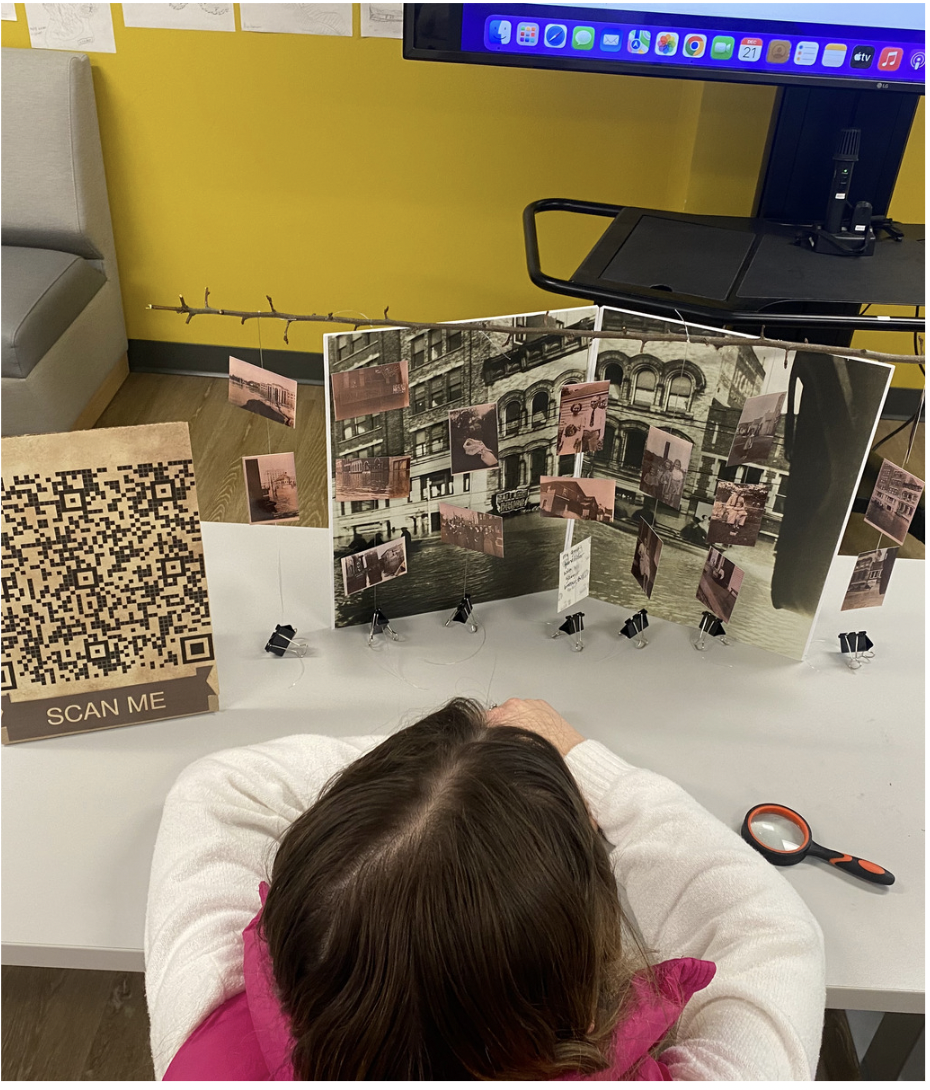

In another installation, a student brought to life her family experience with the Portsmouth Flood of 1937. She directed students to a website that provided background information on the flood, and she showed pictures of her own family members who had been faced with the decision to stay behind despite the destruction, or to pick up everything they knew and move somewhere else.

She wanted to show how difficult decisions are when community connections come into play. It's easy to see a disaster and judge what people should do, but when you actually stand in the shoes of others, you realize how complicated decisions really are.

On day two, students engaged in reflection. In her reflection, about the Portsmouth Flood, Kathryn wrote, "I found that my original perspective was enlightened by others' viewpoints. For example, my art installation focused on a sense of belonging in a community...However, several students brought up external influences that would impact their decisions such as job security or rebuilding the community."

She also wrote that "multiple students had a similar viewpoint as mine regarding family ties and identity...one student commented about...a fear of change and loss impact[ing] them more than the fear of a natural disaster."

Encouraged to revisit their design intentions, students were invited to consider with sincerity what went well and what did not, and determined to reward honesty, Ms. Carmichael and Mr. Martin didn't penalize them for mentioning any shortfalls; in fact, those who were able to identify where their project needed to be refined earned a higher grade than those who manufactured an inauthentic justification for success.

They weren't trying to make themselves look perfect because they didn't have to; this project was about taking a risk and learning from it.

|

|  |

About his project, Spencer wrote, "The results I got from my research were pretty straight forward. It looked like when people listened to their favorite song their stress levels dropped significantly lower than when they used stress relief toys or fidgets."

"If I were to assume this research provided accurate results, I could conclude that interacting with the environment by using positive auditory stimulus would reduce more stress and heal more from emotional suffering than using positive physical stimulus."

"Assuming my research around inducing stress, anger, or emotional suffering was accurate I could also conclude that negative physical and auditory stimulus caused more emotional suffering than negative visual stimulus did. My research likely wasn't very accurate, however, as I had few participants and couldn't monitor and set up each station perfectly."

"I gained extensive knowledge from this process of setting up an installation to conduct research, such as understanding how complicated it is to produce accurate results from research, and how critical it is to think through every part of the installation."

|

| Sienna reported that her "perspective on installations as ethnographic data collection has changed."

"Originally I did not see it as efficient," she said, "now I see how interactive and creative outlooks on research can provide an effective connection tool to participants."

"I believed my installation allowed participants to understand my topic in-depth," but "while...my installations worked well for a classroom-sized class, I do not believe my installation would translate effectively to a larger population with an expectation of reasonably unbiased answers."

"I see the research process in a positive light and now realize how much support and time is invested into ethnographies."

"Input from peers and critical friends allowed for important alterations to my installation, which I believe made it more successful. Overall data collection and set up was efficient, and I believe that my ethnographic installation was an effective process to obtain different perspectives and knowledge."

|

|

|  |

In his reflection about his installation, Jack said, "through this process I learned just how effective, thoughtful and academic art can be."

He went on to say, "I think when writing an ethnography you have a plethora of academic examples of how to go about creating your writing and gathering information."

His installation was not only performative, however, he chose to produce a film with distorted audio for his experience. He asked participants to watch the video and respond to questions about it.

As he considered his experience doing this, he wrote, "I think some of those written examples could aid in the process of creating your installation. I believe it requires more thought and independent thinking to create an ethnographic art piece. It engages a wide variety of people to critique and observe your work because in some ways it makes it more interesting.

"My installation was effective and helped me get the data to better explore my RQ (research question).

|

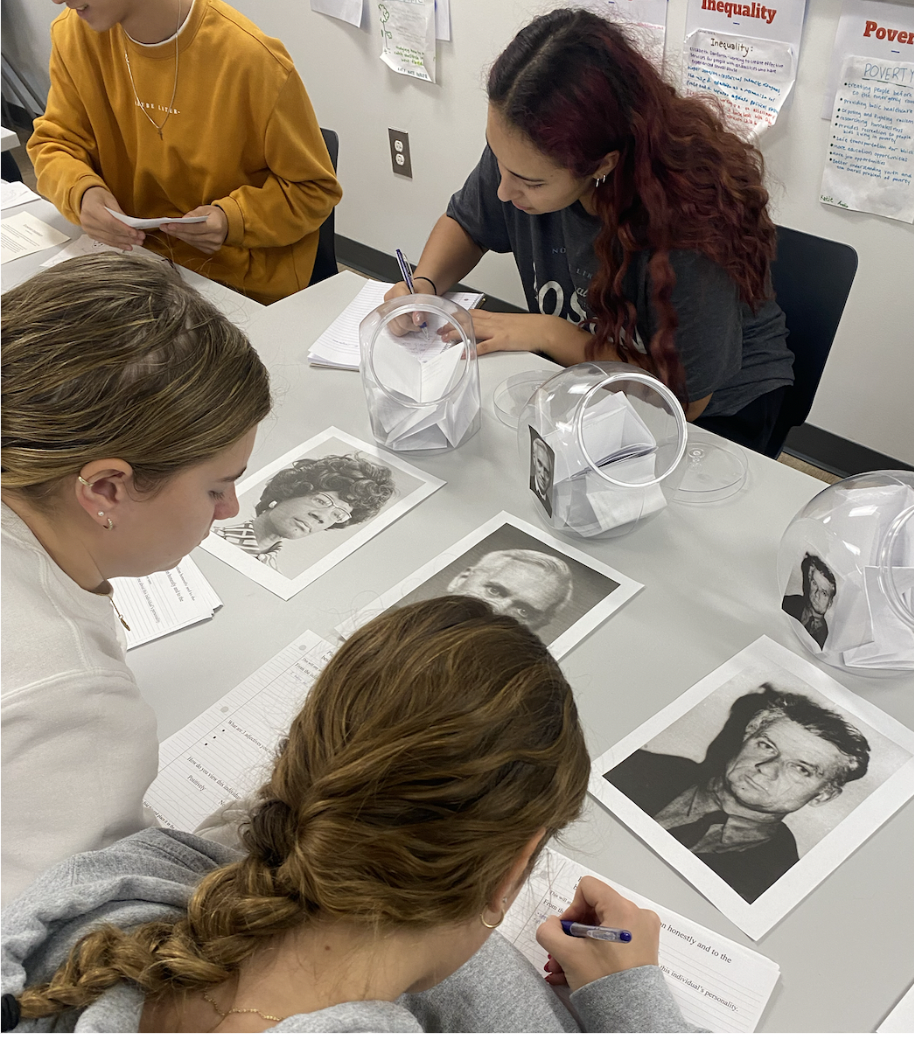

| In Katy's reflection on the way fear impacted behavior and risk taking, she wrote, "Our perspective on fear can shape our outlook on the world and shape our lives for better or worse."

She went on to write, "after conducting my installation, I learned that fear is everywhere. It definitely influences our decisions to an extent even in situations like sticking your hand into a mystery cup."

"For example, a few of my participants told me that the reason they picked a certain cup to first stick their hand into was based upon the notion of luck in their mind. One participant told me she picked a certain cup because it was the second one down, and two is her lucky number. For that reason, she felt better about what was in the second cup, and it felt less fear provoking."

"Another participant told me that his lucky color was blue, so he picked the cup with the blue scrunchy on it for good luck...this decision making process was not something I anticipated, and I was quite surprised by those responses; however, it makes sense that people rely on luck as rationale for making decisions without a prompt or the encouragement of a sign."

"There were other ways people tried to curb the feelings of fear too. Most people closed their eyes when sticking their hand into the cup because it made them less scared."

"Lastly, I found that generally participants felt pressured by fear. When I asked my closing question, "on a scale of 1 to 10 with 1 being not scared at all and 10 being very scared, how scared were you to stick your hand into the cup?" The responses were mixed, but when I compiled my data, I found that on average my participants had a fear factor of 4.5 of 10 doing my installation."

|

By building their exam like this, Carmichael and Martin rewarded what they valued: critical, honest self-assessment. And, because they worked so hard all year to build a culture of trust, students leaned into their invitation, and made themselves vulnerable. They produced detailed recollections of their process and honest assessments of where they succeeded and where they needed to grow. It's pretty inspiring to be around so many people willing to be so open, because it is only through vulnerability that any of us can become better. Students are a quarter of the way through their two year journey, and it's been pure joy to watch Mr. Martin and Ms. Carmichael open up clearings in the forrest, and to see students wrestle with which direction they want to carve their path.